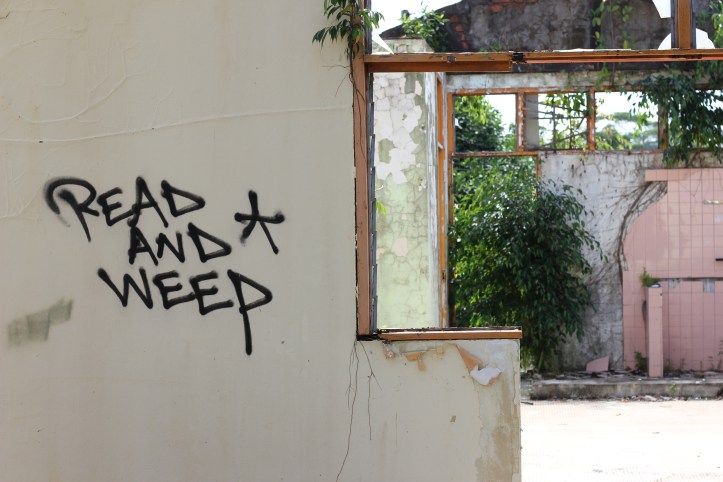

I keep having an internal battle about blogging. Why write here? It seems so vain, so silly, so self-centered. Why am I doing this? Why do I get a dopamine hit when someone likes it on facebook? Is it worth my time? Is this my outlet, my creativity?

Then I got coffee with my friend Martin. We mostly caught up, but in the last ten minutes before I left, we had a mind meld that I have with very few people, but seem to often have with him. He is an absolutely outstanding pianist, and mentioned another pianist that he respected, but didn’t much like, as Martin felt this other pianist played to please the semi-cultured masses. This other guy was a Thomas Kinkade, not a van Gogh. We started to pick apart the tension between creativity and consumption, and in a few moments came up with the following:

- Some create without regard to their audience;

- Some create FOR an audience;

- Some create without regard to their audience, but who find that their audience is everyone.

The first group often end up tortured artists, or are satisfied but ignored. The second are sellouts. The third stay true to themselves, and just so happen to have artistic “success” in the world.

The difference is the motivation. We agreed that we had the least respect for the second group; however, there was little outward difference between the success of the second group and the third, as both could be successful. We had more respect for the first and third groups – those who created out of pure desire to express themselves, their essence, and who may have cared about outward markers of success like popularity, but who didn’t see that as the sole metric of success.

On the walk home, I realised that there are a handful of people who I want to write for: Alice, Daniel, Stephanie, Sunny, Bianca, Meredith, Jacqueline, Mrs. B, and my friends, if they find it. Really, if I can make my little sister laugh, that is the best. I often did things when I was young and the only person whose opinion mattered was her’s; if she liked it, it was successful.

So, like Gatsby painting, I am writing a little, for myself, mostly.

And for Daniel, too. If my sister likes it, fantastic. But I hope Daniel reads these words with an open mind one day, and finds out about me, and knows I love him. That is why I am blogging.

The next week, I got coffee with my friend Chris, and we talked about nationality – particularly, what it means to be Scottish. Since getting my indefinite leave to remain, I have started to question the concept of nationality; I think many immigrants to America can feel American, because the American identity is so belief-based and rule-based. Americans, in my estimation, are in an incredible position, since so much of what Americans are can be traced back to a common set of beliefs, of principles, that we mostly uphold: the constitution, a social contract with each other, freedom. When we talk about the separation of church and state, a tripartite government, or the division between federal and state powers, there may be arguments about how far it goes, but we generally agree that this is how the country works – and we are Americans because we believe in these things.

But even if I get citizenship, will I ever feel British? Scottish? What is it to be Scottish, particularly now, with the possibility of independence looming again? It is particularly interesting to me because…well, I don’t know what British people, or Scottish people, believe or agree upon, and nobody I know seems to know, either. There is disagreement here about how government works, or should work; with devolution, how the Scottish government interacts with the British government, and where powers lie, is still being debated. Plus, Scotland needs immigrants in order to grow…but if there is no definition of what it is to be Scottish, how can immigrants become truly Scottish? How can Americans, Poles, Slovenians, or Syrians become Scottish, in the same way that they can become American? My ILR test was basically a random knowledge test whereby I needed to know the names of Iron Age fortresses and eighteenth-century landscape architects; besides knowing that Britain has a parliamentary democracy, there was very little I needed to know about the civic life of the country.

So in my mind, if Scotland is to move forward, either as part of the union or independently, it will need to have a set of ideals, of principles, that Scots generally can agree upon. Whether it is freedom, education, personal responsibility, etc., we need to know what it means to be Scottish so that immigrants can become Scottish and Scotland can thrive. If this does not occur, then Scotland can either

- Continue to grow based on immigration, but end up with a deeply divided nation of Scots and Others, or

- Stop accepting immigrants and see its population, power, and potential gradually shrink.

And books. Whereas I didn’t finish a single book last month, this month was good for closing covers.

First, Awaken the Giant Within; I have read it before, and listened to Tony Robbins, but this time I feel like I really got it. I have taken the core lessons and distilled them into a list, which I pull out at random times and use. I am excited about this.

Then My Promised Land. I saw Ari Shavit speak at the Anisfield-Wolf book awards in 2015, and it was, without reservation, one of the finest speeches I have ever seen. Once, I was driving with a girl from Cleveland to Chicago, and I realized that she only talked about herself. I started to put out little testers – questions about philosophy, or religion, or politics. It was soon apparent that not only could she not talk about anything but herself, she could only talk about herself and either running or food. It didn’t matter what the topic of the conversation was, her comments would return to her running regimen or her diet. I immediately looked up famous speeches in the car – she was driving – and found that most famous speakers rarely mentioned themselves; Martin Luther King, Junior, was an exception in his “I have a dream” speech, but his dream was more about the dream of every one of his listeners, and not himself. This led to a theory: great speeches should focus on the audience, not the speaker, and the speaker should talk about the listener.

Shavit excelled at this. While his speech was about his book, and Israel, and Palestine, he kept tying it back to Cleveland, to the Jewish community, to segregation, to American history, to the goodness of the diverse booklovers in the room. In one of the most touching moments he brought up the return of LeBron James that year, and the fact that David Blatt, an Israeli, would be coaching the Cavaliers. In a stunning end, he blessed the team and the city, praying that “With your King and our David,” Cleveland would hoist a trophy. There wasn’t a dry eye in my seat, and I doubt there was a dry eye in the audience.

I bought My Promised Land immediately after seeing him speak…but Israel is such a giant topic, and would this be the right introduction? Why not start with a history of Judaism, or with the oft-recommended From Beirut to Jerusalem? Then, right when I was ready to sit down and start it, I read that Shavit was embroiled in a sexual harassment scandal, and I suddenly was repulsed by his book.

Still, I wanted to learn, and couldn’t really get into Friedman. After a few false starts, I picked it up again and started reading it.

The smell of sand and orange blossoms filled the room. I heard the Palestinian cattle bells and then the roar of airplanes overhead as Israel destroyed the Egyptian air force, and watched as kibbutz members learned to dig wells and assemble rifles. I felt the sweat of Tel Aviv nightclubs and heard waves lapping against the shore and heard the screams of Palestinians being tortured, begging for mercy, giving names and addresses of their friends, who were then kidnapped and brought in for nothing until they, too, confessed. In two chapters on Lydda and housing estates, he shows both why Israel is the perpetrator of terrible acts that have clear echos of Nazi Germany, yet why the nation of Israel must absolutely exist, and why it deserves our support. The reader is left with a better understanding of why Israel is the way it is – the major events, from founding, to the Holocaust, to invasions, to land seizures, to the next generation, that have made this nation of immigrants from around the world into a potent, vibrant nation.

So despite Israel’s flaws, and the personal flaws of the author, I was floored by this history, and recommend it to anyone who wants to better understand the Middle East.

And the month ended with When We Cease to Understand the World. I bought this in a Kindle Daily Deal, on a whim, not thinking I would read it until I found out if it won the Booker Prize, but then read it a single day. It is stunning, and exceptional, and so beautifully translated – I wish I could read it in its original Spanish, but in English, every paragraph has the rhythm of poetry, and the forward momentum of a Dan Brown novel, propelling the reader forward, forward, curious to learn more and know more. Plus, there are a lot of details that are factual, and, on checking, I now know way more about science and mathematics than I did before.

Knowing the Booker judges, it will probably lose – it is that good.

And Daniel.

He is now negotiating with us. It is mostly him wanting to do things – for example, he may want to scoop coffee grounds into the Aeropress, to which I say no, and then he says, “See it though?” Then he peers into the coffee canister, and comments on how full or empty it is. Sometimes the compromise he seeks is unrelated to the original request; he says that he wants to fill the kitchen sink with soapy water, and is denied, and so he asks for yogurt.

He is shy in so many social situations – he loves inanimate objects, and animals, but is scared of people, of strangers. Granted, strangers are scary, particularly the old women at Marks and Spencers who always try to touch him, and the couples on the street who stare and smile unselfconsciously at him, and the drunks outside bars who wave and shout to get his attention.

And recently, he has started to ask for bedtime stories from me. Usually he just feeds to sleep, but then one night he told Alice that he wanted me to tell him stories and sing songs to him. The first time, I sang him Indigo Girls and They Might Be Giants songs, softly, and told him a story about us going on vacation until he snored. The second night, I was at Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu for his bedtime, and I was walking home when Alice texted me: “Daniel says he wants daddy to sing stories. So I told him he could play in his room until you come home.” It was two hours past his normal bedtime, so I started charging up Leith Walk. When I got in, he was standing in his cot, and Alice was at the end of her rope, so I sat down next to him and told him about being born in Lorain, Ohio, in 1979, and how we lived on the corner of a bland block; how one day, when my dad got home from a shift at the hospital, my mom apparently said to him, “I wouldn’t mind if we moved.” The next day, they put the house on the market, and a little while later they moved to El Cajon, California. My dad had a medical practice there, and we more or less grew up in his office; then I went to college at Pitzer, in Claremont, California.

Then I started telling him about something that happened my senior year. I was president of the student body, and one day, I was walking between Mead and Holden dorms and, ahead, saw Professor Jose Calderon talking with Andy Beetley-Hagler. I knew that they were the driving force behind trying to get the dining hall workers to be able to vote on forming a union, but I had never really paid attention to the movement – I knew lots of the activists, but I didn’t really care about unionization, per se. They had been agitating for years, too – hunger strikes, taking over administration buildings, etc. The workers wanted to unionize, but in order to do so, the administration needed to allow a vote. In order to get the administration to allow a vote, the issue needed to come up before College Council, and then it would be brought up to the Board of Trustees. The activists really, really wanted to get the issue in front of the College Council, but the President, Marilyn Chapin-Massey, kept blocking them at every turn. Also, as a student politician, I was tainted by association – I was part of the power structure, so I don’t think they liked me very much.

But something inside me made a connection when I saw them walking and talking between those dorms.

In my memory – which is completely fallible, particularly at twenty years removed – I walked up to them, and they looked at me and stopped their conversation. My introduction was awkward; I knew that they wanted this issue to be voted on, and neither the President nor the Dean of Faculty would ever put it on the agenda of the College Council. However, what wasn’t widely known was that there was one other person on campus who had the ability to put a bill on the agenda of College Council. That person was the President of the Student Senate.

Me.

And I wanted to help.

I am not sure as to my motivation – again, it wasn’t that I was particularly pro-union, but maybe it was that I wanted to represent the students, or to stick it to the administration. Maybe I wanted the activists to like me. Maybe it was a combination of these things. Regardless, I could do in a week what they had been trying to do for years.

Professor Calderon almost lost his famous poker face behind his glasses. “I think you two should talk,” he said, and then, without another word, adjusted the books under his arm, turned, and walked away. Andy and I walked to my dorm room in Holden and I outlined the plan: I would draft a bill in the Student Senate, and James Merchant would introduce it. It would pass unanimously, and then I would add it to the agenda of the College Council. I would need him there to speak in support of it, with as many other students as he could find.

I am 99% sure he still didn’t trust me or like me, but he agreed. That Sunday, at Senate, it all happened.

There was a Council meeting in late November or early December; this must have happened, then, in October. I sent an email to both President Massey and Martha Crunkleton, who was the Dean of Faculty, but she was in the process of resigning, so, if my memory serves me correctly, Paul Faulstitch was coming in as acting Dean. That week, I got a call from him while I was scrambling to get my homework done before class.

“You can’t put this on the agenda,” he said.

“Why not?”

“You don’t have the power to do it.”

I took down the student handbook, the faculty handbook, and the bylaws of the College Council from my shelf, and for eighty minutes tried to get him to look at his copies of these documents to see that I did have the power. I know it took eighty minutes because I missed macroeconomics with Linus Yamane, which meant I couldn’t pass notes to the Scripps girls in class – a habit he later commented on. It is funny how much you find out about your teachers later in life – like realizing that they are humans, with outside lives, and they know more about the students than the students ever believe.

Faulstitch steadfastly refused to look at his copies of the bylaws, and kept telling me that only Massey could set the agenda. I kept reading the passages out to him saying, in clear terms, that the three people who had the ability to add items to the Council agenda included the President of the Student Senate, but he kept saying that none of these documents said anything of the sort. Finally, he agreed to open his faculty handbook; he went to the page that I specified, and the paragraph, and read it out loud, and I asked him what it meant.

He was silent for a moment, trying, I assume, to formulate some sort of interpretation that proved me wrong.

“You can read it again if you need to.”

Finally:

“You can add items to the College Council agenda.”

“Why thank you,” I said. “I truly, truly appreciate your time.”

Click. I thought of the girls who were now walking back to Scripps, and thought that success in this fight could come at a significant personal cost. Was I willing to pay that price?

When the meeting came, the room was packed – I don’t think they had ever had such a well-attended College Council session. It was standing room only – besides the Council, the entire Senate turned out – 60 students – plus activists from all five colleges, and some of the dining hall workers who we were fighting for. I remember looking around the room and thinking, “Sweet Jesus, this is serious.” I saw Andy, and tried to smile at him, and he nodded. He was great at nodding. One of the workers, a tall Mexican with a giant black moustache, in his kitchen uniform, looked nervous. I had the brief thought that they weren’t used to meetings, in board rooms, with cucumber water and Robert’s Rules of Order.

And: if we won, we should get them copies of Robert’s Rules of Order.

We were the last item on the agenda. After the other business, but immediately before our bill was introduced, Massey said, “I have just received a note that says that we are about to experience some rolling blackouts. In the interest of everyone’s safety, we are going to end the meeting now.” She banged the gavel and slid out the back door.

There was outrage, but I was somehow at peace with it. They had nowhere to go but to make up a rolling blackout. Well, maybe not make things up; it was 2001, and California was being hit by rolling blackouts in late afternoon, and this was the late afternoon, so it was entirely plausible (and, if memory serves, there actually was a blackout an hour or so later). I walked over to Andy, and the other activists crowded around us, and I felt good. They were worried that this was the end, that it meant we had to give up this route, but I explained that Massey could delay it, but we would be back in January, and it would be the first item on the agenda. Someone translated it into Spanish for the workers; they looked frustrated, but they still knew we were supporting them.

When we got back from winter break, we got word: we would not be the first item on the agenda. The Board of Trustees had agreed to let the vote on unionization go forward.

When the workers voted, it was overwhelming: they had a union.

We had won.

One of my most treasured memories was walking into the dining hall after the vote. Eloisa Ramirez, who I called Abuela, came up to me and hugged me tightly and said, “Thank you, thank you, thank you, I am so happy.” I don’t think I will ever forget the feeling of her little arms and her face against my chest, her eyes behind coke-bottle glasses beaming. We had won. It makes me cry every time I think about it, including right now. I only learned this week, from Professor Calderon, that Pitzer workers have had a union for 20 years, and this means that the workers are employed year-round; Pomona workers got a union later, which gives them the same right. Claremont-McKenna, Scripps and Harvey-Mudd workers are only employed for fall and spring, and have to look for work in the summer to make ends meet.

I could have told Daniel about how later that same spring, the same activists were protesting another issue and had chained themselves to concrete blocks. Joanne asked me to come in support, and I brought food and water from the dining hall and gave it to them – they were unable to use their hands to eat or drink. I remember Joanne looking at me and saying, “I didn’t think you would actually come,” and realizing that she didn’t know I cared about her, and how I suddenly felt like I had a new friend. And I could have told him how we were told not to shake Massey’s hand at graduation – the monitors said that if every student did so, it would take too long for the procession to finish, but I ignored them. I was the goddamn President of the Student Senate. I shook her hand, then smiled, and then hugged her, and – on a bet with a couple other students – licked her right cheek, from her chin to her cheekbone, then ran away as the other students cheered and she wiped her cheek with her gown sleeve. I could have told him that the year I graduated, she retired and moved to Paris, where she still lives as an artist, and Dean Crunkleton and Dean Dave Clark both quit. I don’t know where they are. Pitzer started with a clean slate.

But by then, despite my riveting storytelling, Daniel was asleep. I checked his breathing, told him I loved him, and then closed the door as softly as I could behind me.

Daniel, if anyone ever asks or wonders: these are the bedtime stories you are growing up with.

Your writing is skilled and beautiful to read, your thoughts are stimulating and the way you two are raising Daniel is rich and touching. I am deeply honored to have known you from your teen years and to have witnessed the net growth of your life so far … I am deeply honored to be included in your list of readers.

LikeLike

[…] day I had something to celebrate – I think it was when the administration backed down and we won the right of dining hall workers to unionize. I had gone to my room and taken out my grey and green Pitzer insullated plastic mug and poured a […]

LikeLike