I used to think that nobody I knew could die. Even until I was in my 20s I honestly believed that I, and everyone I knew, was invincible. I credit my upbringing: one of the defining features of 1980s Southern California was its absence of aging, of death. I was surrounded always by youth, in a Siddhartha paradise. It was as if we hid the old away, out of sight, and the dead never existed at all. It wasn’t until I was in my 30s, when I went on a long run while visiting home in the winter, that I accidentally found out that El Cajon even had a cemetary; if you had asked me where people were buried, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. Cemetaries existed in Dickens and Twain, their books and times, but not in the California of my youth.

Then, in my sophomore year, I was a residence assistant in Sanborn. I think it was after winter break that one of the other RAs, Andrea, didn’t come back; we got an email that she had suffered from a severe eating disorder, had been admitted to a hospital, and had died. That was all – just an email, students@pitzer.edu. Practically, the team would need to recruit a new RA to fill her place, and the supervisor would need to get a new set of skeleton keys made. I think if I was to ask the people from my class about it today, nobody would be able to tell me her last name.

Then, ten years later, Pito died. Was killed. Shot in the stomach. I remember the hours after Carl called, how confused I was, how tragic it all seemed. I kept imagining his last few moments; Carl had said that being shot in the stomach was particularly gruesome, that it meant he had been in a lot of pain when he died. That afternoon, I was, in a bizarre twist, supposed to go to a shooting range with my friend Asim, with thoughts of violent gun death hanging over me. I have no idea why we were even going; it wasn’t like I loved guns or anything, and, given the circumstances, I probably should have called it off. I told him about the killing, and how shaken I was, and then we started shooting. I don’t know if he had ever held a gun before, but for some reason he started waving a pistol around the shooting range, pointed, at times, at me and other people, including the instructor. For a dark-skinned Muslim in a shooting range in a conservative part of Ohio in 2008, this would have normally struck me as a dangerous thing to do; with Pito’s death on my mind, it also struck me as incredibly insensitive. When I told him to stop, he pointed it at me again and said, “It’s not loaded!” When the shooting range instructor – an ex-Marine who carried a concealed and loaded Springfield Armory 1911 at all times, and who had gone through thousands of hours of training – told him to stop, and to never point a gun at something he did not intend to destroy, Asim sulked and muttered, “It’s not loaded.”

As I drove home, I realized that I had lost two friends that day.

A few years later, in my sailing days, I arrived at the dock to find that the boat I usually crewed on was missing. George, one of the other regular crew, said that Richard – the owner of the boat – was bringing it back, and we would be out in time to race, but it would be tight. A few minutes later, the boat motored up to the slip; we helped Richard tie up while a man I had never seen jumped off the boat, said “Hi!” and ran away.

“Who is that?” I asked.

“That’s James,” Richard said.

“Where is he going?”

“The car. He’s carrying.”

“What is he carrying?”

It turned out that James was the head of security for the Nation of Islam, and was carrying a .45, which he was fully licensed for. When Richard found out, though, he told James that under no circumstances could he have a gun on the boat, and that even though everyone else on the boat would have knives at all times, these were practical, for sailing. Richard explained that James would be under no threat from any of us, and that the other people who raced yachts were unlikely to attack him; this was the goddamn Chagrin Lagoons Yacht Club. James finally accepted the fact that if he wanted to race on a yacht with us, he would have to leave his gun in Richard’s car.

Not even a week later, George called me.

“I just thought I should tell you that James got shot.”

“Who?”

“James, the guy we sailed with. He was shot.”

James’ daughter had been in a fight with her boyfriend; maybe it was physical, I don’t know. James felt obligated to step in between them, at which point the boyfriend had pulled a 9mm and emptied it into James. Thinking James was dead, the boyfriend had started to walk away, at which point James, prostrate and bleeding, pulled out his .45 and shot the boyfriend once, killing him. James had survived, and was expected to recover fully, despite his wounds.

“So that answers that question, anyway,” George said.

“What question?” I asked, thoroughly confused.

“Whether a 9mm is better than a .45.”

Which is actually a question.

I think to myself, often, that the America I know is so different that the America portrayed on the worst television, or the best movies. In the best parts, we are surrounded by celebrities, and in the worst parts, we are surrounded by violent, gun-toting maniacs. The America I know and often miss desperately is both of these things, and I often felt as if they each sat on my shoulders, not vying for my attention so much as using me as a meeting place.

I got a message on facebook in March, though, from some guy I had never heard of, with the suspicious name “Benny.” He said that Alex, the only facebook friend we had in common, had died. My first reaction was to cry, a deep pain in my chest. Alex wasn’t even 45 – what had happened? Suicide? What if I had called him; what if I had been a better friend? And then I decided to question the messenger. Was this some sort of scam? What did this “Benny” have to gain from me thinking Alex was dead? My brain alternated between grief and disbelief; I waited to see if “Benny” asked me for $5,000 for funeral expenses, or to sign some form and send it to him.

To check his story, I messaged Hema and Brita, who Alex and I had lived with; had they heard? Hema messaged me back – no, they hadn’t. The plot thickened. On a Monday afternoon, I found myself on the phone, 5 p.m. GMT and 12:00 EST, talking to Hema, my former suitemate, whom I hadn’t seen or spoken to in 24 years. She was suspicious, too, and asked how I had heard, and I told her about this random guy, and she said, “Benny! I totally remember him! They had dinner together every night.”

We kept investigating…and then a public post by Alex’s mother confirmed it. Benny was real, and legitimate. We set up a WhatsApp chat, and shared information as we got it – on the death, the funeral plans, how Alex’s family was doing. Someone asked whether we could do anything for Alex’s widow or children, but we received no response from them. Then Benny came up with an idea: he wanted to dedicate a bench to Alex, but it was prohibitively expensive in San Francisco – like $6,000. Instead, he decided to buy a brass plaque – $15, maybe $20 – and affix it to a bench without permission. He thought – and I agree – that Alex would have appreciated that gesture, and the parsimony. Did anyone else want to do something in their city?

I thought: go big or go home.

The memorial service was subdued – a few speakers, some music, and then it ended. I watched on Zoom; Benny, Hema, Hayden, and Jackie all went in person, Hema flying out from Florida, Hayden from Portland, and Jackie getting an Uber from Claremont. I burned incense during it, and felt overwhelmingly sad, although Benny’s speech was beautiful and inspiring and reminded me both of the kinds of friends I had when I was growing up and the ones I want to have as I grow old, if I grow old. The service was on a night when Alice was gone with Nick to see her family and I was alone with Daniel, who was asleep, and I went into his room afterward and listened to him sleep.

I used to say – I still sometimes say, but less seriously now – that I am immortal until proven otherwise. Maybe now that my youth is over, and I am out of California – maybe now is when I hear the echoes of death more often, when people start getting in touch to let me know, when I scan the back of the alumni magazine and recognise names, or faces in photographs of photographs, when I start to have to decide: whose funeral is worth a plane trip and a few days off work? Or do I, like Meyer Wolfsheim, “learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead,” and decide that “After that my own rule is to let everything alone”?

Or both?

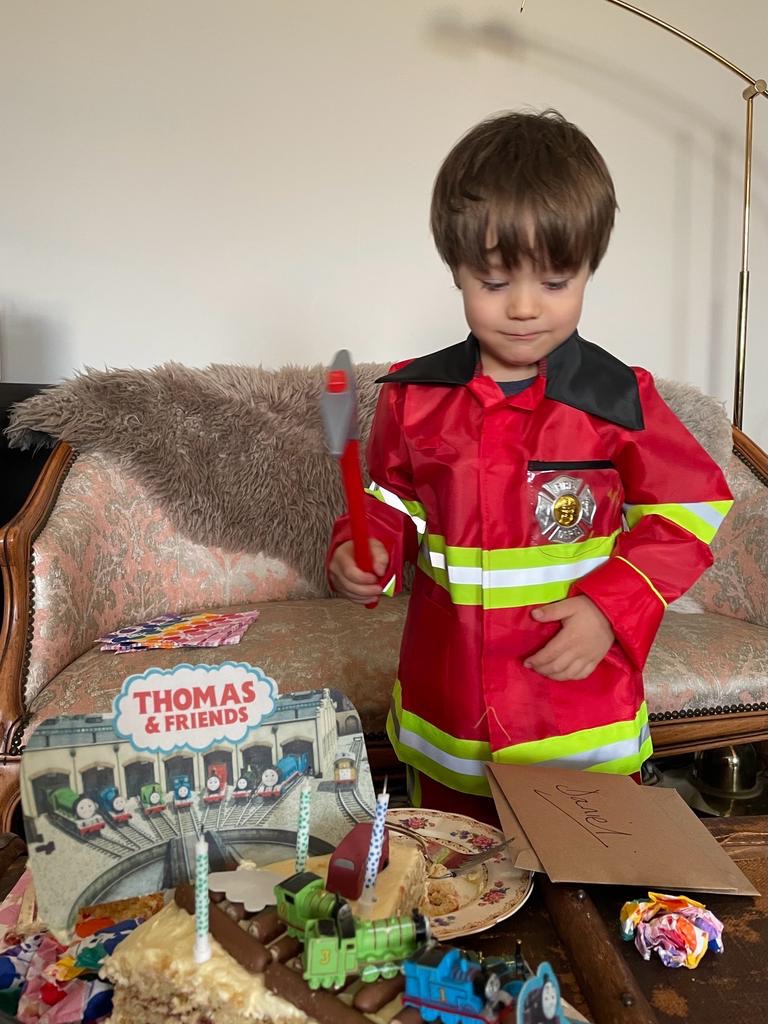

And somehow, in March, Daniel was four.

Sarah told me to enjoy their youth, as “the days are long and the years are short.” Suddenly, Daniel is learning about jokes, about sarcasm, and developing genuine enthusiasms beyond construction and emergency vehicles; he shares his toys with joy, cries if he can’t play with Nicholas, and cuddles in bed with me while we watch Singing in the Rain, which is currently his favorite movie. (He also claims to be a better dancer than Gene Kelly, which is technically true, I tell him, as Gene Kelly and Donald O’Connor are both dead.) And manners: when he really, really doesn’t want to do something, and is crying and kicking his feet, he will scream, “NO THANK YOU!!! NO THANK YOU!!! I REALLY DON’T WANT MY HAIR WASHED!!! NO THANK YOU!!!”

For his birthday, we took him to Diggerland, which is a theme park, but with construction equipment. I have more respect for the guy who came up with Diggerland than I do for Walt Disney; he absolutely nailed his potential customer base. We…dug things.

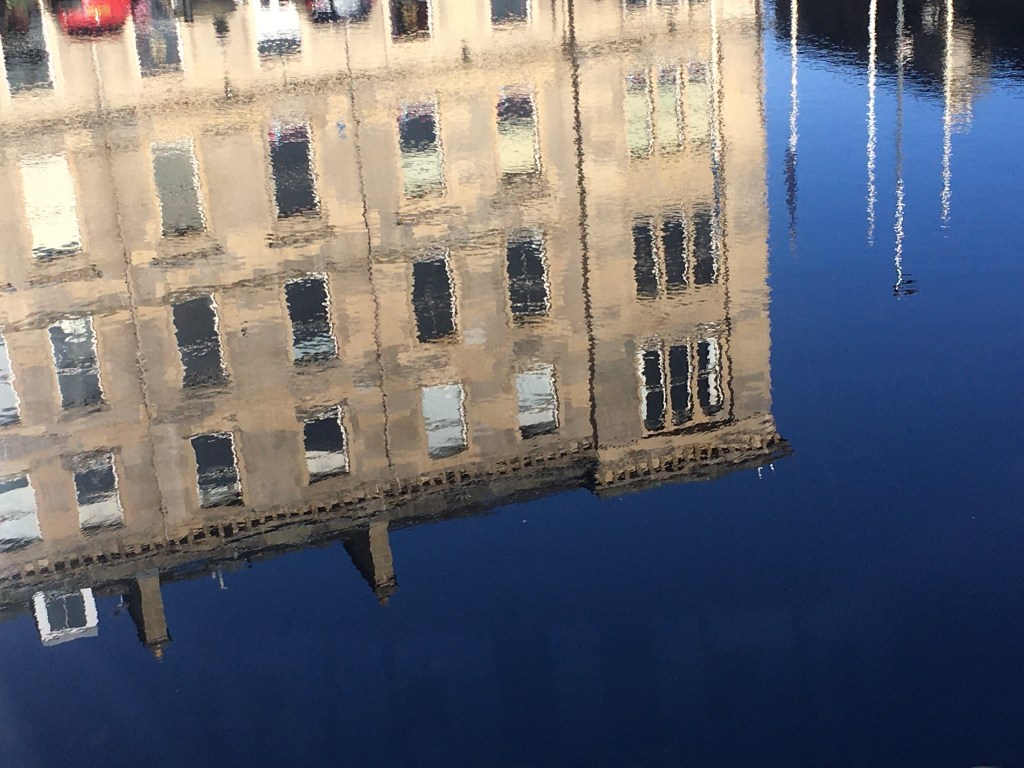

Coming back into Edinburgh, we were walking home, laden with bags and excited to see familiar surroundings. A hundred yards from our front door, I heard someone say, “Andrew! Andrew!”

There’s a way of saying a name that indicates that you just want to say hello, and that you expect to see the person again shortly; it is casual, without much expectation. Sorin or David might shout it across a sidewalk, and we will hug and chat for a minute and then leave, knowing that we will see each other again within a week or two. This woman was saying my name in a way that implied surprise, and made my shoulders tighten. I looked around, and she was standing on the sidewalk, smiling at me. I am terrible with names; there were people in Cleveland who I had spent hours, days, with, who I had to introduce on stages, and whose names I could never remember, but after fifteen years, I was able to say, with equal surprise, “Amanda?”

My second least favorite ex-girlfriend’s best friend.

Who, to be fair, is, and always has been, a wonderful, thoroughly kind person – the kind of midwesterner who could never be described as anything but nice. She was in town with her husband and son; she said she had seen Daniel and Nicholas, and was thinking about how cute they were, when she saw me and realized she knew me. They had been in Edinburgh for a week and were just about to leave; exhausted, and surprised, I gave her a few recommendations for places to go, and my phone number, and then Daniel said, “When are we going to leave?” and we hugged goodbye.

But she got in touch that evening, honestly wanting to see me again, and we met for coffee the next day. On the way over, I was actually sad that I couldn’t show them all the Edinburgh I enjoy, but then I thought that maybe it was for the best. I remembered when I was living in Barcelona and my dad visited and I had to think of things to show him. My tour for him started with the bakery across the street, where, every day, the baker toasted the previous day’s pastries and sold them in cheap bags of crunchy bread bites; I showed him the spiced ones I liked, and we fed a few pieces to pigeons in a tiny patch of grass near the metro station. Then, we rode the metro to Espanya, which had fun signs, the old ones where every space had a full alphabet and set of numbers that could flip rapidly to show towns, times, and warnings. We walked from there to Montjuic, and then down to El Corte Ingles, then to Gracia, where we wandered the streets; I would have bought him a bag of churros, a rare treat for me. I showed him my old gym, DiR, the one I couldn’t access anymore, so I just showed him the front door, and then we went to a cafe that had jamon, except he is vegetarian so didn’t have any, and he doesn’t drink coffee, so he probably had water and maybe bread. We talked about my sister’s upcoming wedding walking through an industrial area, then went to Aldi and got a baguette and strawberry jam and brie, and went back to my apartment and made sandwiches for dinner. That was the tour I gave him of one of the most exciting cities in the world. What would I show Amanda, or any other visitor, of Edinburgh? Would I explain the complicated algorithm I use to determine which recycling bins to use, depending on the day, whether I was running or going to the gym, the size and type of recycling, where I was working, and whether I needed to get any fresh vegetables for dinner? Would I recommend Dave’s restaurant, except it only has two tables and is only open for dinner and doesn’t serve alcohol, so I can only go when Alice is travelling with the boys because otherwise I am helping with bedtime? The thrift stores that have the best books, or the one with the extensive selection of fabric scraps?

It was irrelevant; we only had an hour for coffee at their hotel. We caught up, and then I had to go back to work, and they had to catch a train. But at the beginning of the conversation, I confessed that my biggest question was “Who are you now?” Because fifteen years is a lifetime. We reflected on the paths our lives had taken, and I tried to imagine me through the eyes of someone who hadn’t seen me for fifteen years; what had we both done? What had everyone done? How can anyone ever not be curious about the human experience when this sort of thing happens every day – billions of lives being lived with our own memories and thoughts and impulses, pains and pleasures? What did she imagine of my life, and what could I never imagine about hers?

Which is, I think, the point of A Visit from the Goon Squad.

I kept seeing this in thrift stores, but only got a copy when I saw it had won a Pulitzer; I needed fiction after Master of the Senate, and thought this would be light and fun. Oh, how wrong I was. It is a brillliant, brilliant piece of fiction – a bit like Olive Kitteridge, in that it revolves around a single, but not main, character, and is all about intersecting lives. Whereas Strout dominates the third person, though, Egan is adept at different narrators and styles and nails every single voice perfectly; there are so many stories that come together in different ways that I was constantly awed at her skill, and even now, thinking about plot lines, I am realizing what small events meant in the grand scheme of the world she created. It is well worth a read.

And then I picked up the only Caro book I had not yet read, The Passage of Power. After I closed it, and let a few days pass, I suddenly realized that I had new confidence as a reader. I can perform the physical act of reading, but until this year I haven’t felt like I was able to read good books, or devote myself to them; was what I read actually worth reading, really? Or, perhaps, I was not sure that my reading matter was worth the time. (Back to Amanda: I saw that she had a book, and asked her what she was reading, and she dismissed it as something light – Mary Higgins Clark or something similar. My immediate thought was: FFS, it’s a beaten-up, dog-eared solid paper book! That in itself is glorious, in this day and age!) After finishing every Caro book, though, I suddenly thought: I have nothing to prove. I can stick to a theme, spend time on something long and dense and deeply interesting, and I can grasp it; I can read.

Then I immediately started and finished Barbarian Days. At first, I was completely uninterested. Surfing was always in the background when I was in California; I never had a real interest in it. Finnegan, though, describes the sport with such beauty that I was entranced, and it made me realize that the mastery of surfing, the attention to details, elevates it to an art. But isn’t that true of anything that people have a passion for? I often think of the “eccentrics” – people who are fascinated by trainspotting, for example, or birds, or collecting stamps. One can see the trainspotters at Waverley, photographing each engine, writing down carriage numbers, checking time tables and watches and making notes. Who am I to judge them for their passions? I simply just don’t know enough to stand next to them on the platform.

Then I got through The First Tycoon, about Cornelius Vanderbilt – of this, I can only say that the Pulitzer pool this year must have been pretty weak.

I then veered away from the Pulitzers: first, listening to the audiobook of Obama’s A Promised Land. Maybe I justify it by saying he won a Nobel? It was a wonderful memoir, but the audiobook was forty hours of his voice – a voice I miss. It was truly wonderful, and got me through many early morning runs, and made me hopeful again.

And finally, Overruled. For full disclosure, I am friends with Sam, which is why I read it – we were going to have lunch together, and I didn’t want to admit that I hadn’t read his book. As I work for the government, that is as much as I can say, but I can still recommend it, with some criticisms, which I brought up with Sam and which we talked through. For anyone who wants to know about what British democracy looks like from the inside, from an Oxford law professor’s view, from the standpoint of someone on the front lines of constitutional law, I recommend this book.

And four months of sobriety. I have been playing around with limitations recently – not drinking alcohol means I drink a lot more water and mint tea, which is wonderful. I am going to avoid spending money except on lunches at the Club or Saturday lunches with Alice and the kids; committing to not spending money means I don’t look for things to buy, and don’t spend time window shopping, which means I have more time to read or write or run. Not wearing jeans means that I wear slacks, and think less about what I will wear every day. Not eating sugar during the week means that I eat more vegetables. I want to create more of these intelligent limitations, so that I can excel in other ways.

And that was March, and April. Spring again, and death.

There is one way in, and one way out.

To the future.

So very nice to read this. I always feel like I’m on a relaxing, enjoyable stroll with you when I read your stories.

This time, your opening was timely, in that I lost one of my longest lasting friendships with the death of a dear wise, funny jurist. What a rush of memories from over 50 years. Well respected and well loved. We had many good times together, especially when we were young and could hang out over good long dinners.

Daniel is four! Ah, this is the perfect antidote for temporary sadness. I laughed out loud when I read “No thank you!!! I really don’t want my hair washed!!” Well, one day he’ll appreciate the luxury of having a good barber wash his hair.

In the meantime, love to you all.

LikeLiked by 1 person