One Monday morning in May, the fifteenth, I had an exceptionally strange dream. In the dream, it was 2000, in the summer. My mother had purchased a plane ticket for me to fly from San Diego to Los Angeles to spend my birthday weekend there; why I might fly, or why I would go to LA, or why my family was there, is a mystery in my awake state. My girlfriend in the dream had asked me to buy a plane ticket to San Francisco for the same weekend, which I did, not realizing that there was an overlap; I was conflicted, suddenly, over who to go visit. At the same time, I was trying to figure out if I should go back to Pitzer for my final year, or if I should take a year out and work, then return. When I woke, I had just realized that if I took a year out, I would not graduate with my class, but with a group of people I barely knew; I would not see many of my favorite people again, perhaps, and certainly not all together, living on the same campus. I was still weighing the pros and cons when I woke up, and, I suppose because of the intensity of the dream, I thought it was still 2000. What should I do? I only slowly came to realize I was not in San Diego anymore, but I didn’t know why; I had to count the years up, one by one. 2007? No…2012? No…more and more incredulous, I got to 2023, and stopped. 2023! Imagine that. And living in Scotland! How did I get here? What myriad other paths did my classmates take – the ones I was so scared of never seeing again, and who I never actually saw again after graduation? Twenty-three years, lost in the flash of waking up! Babies born when I was graduating from college are now graduates themselves, legally drinking, looking for jobs, suffering through the indignities of whatever young adults suffer now.

About the youth of today: recently, I saw a sign outside of a charity’s office, soliciting donations for their cause. I should have taken a picture of it. It had a young woman on it, and a description eliciting pity: she was 22, and according to the sign, after she had paid rent and food, she didn’t have enough money to go out with her friends. That was the call for help: give money so this young woman can go out drinking.

June.

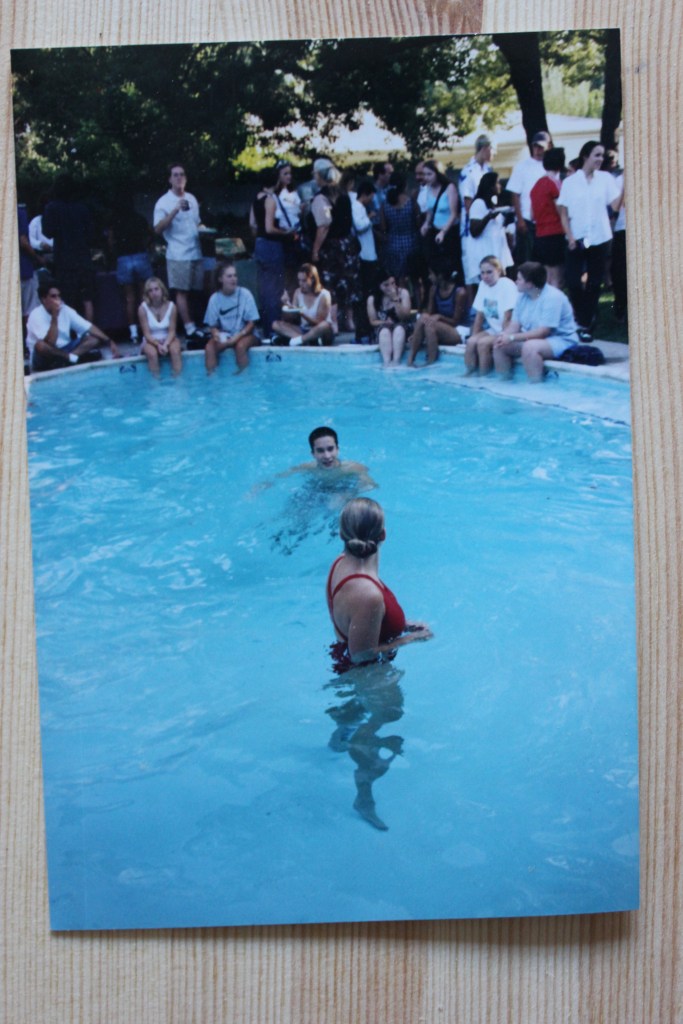

When I first arrived at Pitzer College, in August 1997, there was a week where only first-years were on campus, just to let us get used to being there without all of the intimidating upper-class-people to contend with. As part of the introduction, the President of the college, Marilyn Chapin-Massey, threw a party at her house. Many of the first-years showed up to eat catered food, drink soda, and see all of the other new adults who had flown the nest just days before.

I was in the back yard speaking to the Dean of Students, Dave Clark, when he mentioned that it was supposed to be a pool party, and he was disappointed that nobody was even dipping their toes in the water. I occasionally have inspired moments where the exact right thing to do pops into my head, and, somehow, I do it; this was one of those times. Back in the days before cell phones, I handed him my wallet, which he took, not understanding its import, and then I took my shirt off and jumped in the water.

I remember coming up to cheers, and suddenly it was a pool party. Other people stripped down and jumped in, too; some others, without swimsuits and wanting to stay dry, sat on the edge with their feet in the water. When I got out, Dave handed me my wallet and said, with a broad smile on his face, “You’re going to be fun.”

For some reason I wanted to go home early, so I started walking back to campus alone. I was passing a dorm room at Claremont McKenna, the college across the street, when I heard music – a flute – from the second floor. Dripping wet, holding my wallet in my hand to keep it dry, I walked up the stairs to an open door; a girl, obviously a first-year like me, was playing the flute. She looked up at me, startled. Probably petrified.

In a situation when I look completely absurd, I am at my most charming, most ingratiating, most charismatic; this was a charismatic day. I don’t know what I said to her, but we got to talking, and exchanged numbers. I ended up meeting the guys in the next room – AJ Prager, who was a sincerely kind person, and Preston Farmer, who I still write letters to regularly – and we all became friends. She was from San Diego, too; was half-Asian, too; was curious about the world, too. We were friends through college, and after graduation, we both moved back to San Diego. We did all sorts of young-person things – in order to leart to cook, we decided to make dinner together once a week; we mixed our friend groups, and learned to throw adult parties; we supported each other through breakups. Then, she joined the diplomatic service, and I moved to Cleveland for law school; she and her husband visited me there for a night, back in maybe 2013. I remember walking down East Fourth Street with them, drunk after dinner at the Greenhouse Tavern, laughing at how amazing old connections can be.

Then, in March, she emailed me: she was doing a tour in Islamabad, and she and Chad wanted to come to the UK for a break. The only things they wanted to do were to walk outside without the threat of attack, eat pork, and order alcohol in restaurants.

And so, 26 years after we met in that dorm room, she was eating dinner in my kitchen in Edinburgh.

While they were visiting, my friend Kelly, who is from Scotland, messaged me that she was in California. She mentioned that Americans in America are different than Americans in the UK. One of the things she pointed out: there was a sharp difference in the questions that people asked each other. She would ask questions, and Americans would give her short, brief answers; she would wait for longer explanations that did not come, and so to fill the space she would ask another question, which would get a short, brief answer. When Americans she barely knew asked her questions, the questions were, she felt, deeply personal, requiring long explanations and potential embarrassment or discomfort on her part…and often she gave short, brief answers, out of a desire for privacy.

It was strange to hear that, because while Melissa and Chad were here, I fell into the easy conversational rhythms that one would associate with old friends, but which felt different to me, because I had only met Chad once, and I hadn’t spoken to Melissa in years. But then I thought of my conversations with other Americans recently, and how different the interactions are, even with people I barely know. I came up with this theory:

- It is not just the words and pronounciations that are different on different sides of the Atlantic; the rhythms of speech are different. British people interrupt each other a lot more and expect those interruptions, whereas Americans tend to listen a lot more, then respond; it is like we are conditioned to different cues in a conversation.

- Americans tend to ask more open-ended questions, and answer fully; British people ask closed-ended questions, but answer fully as well. However, wher British people ask Americans closed-ended questions, the Americans answer in a manner they feel is appropriate – a yes, a no, the color “blue.” In American minds, this isn’t being rude; it is being polite by not over-answering a question. There was a guy at Pitzer who, if you asked him “what’s up, man?” would answer thoroughly, over ten minutes, in a nasal monologue, everything on his mind and in his life; people finally learned to not ask him anything.

- My suspicion is that the closed-ended questions here have the effect of giving the respondent the opportunity to answer in as much depth as they wish – “Yes” could be appropriate, but “Yes, and…” would also do. It is intended to respect the privacy of the person answering, and give them the opportunity to answer as much as they feel comfortable.

In my interpretation, both approaches are completely intended to be polite. They just end up being incompatible.

This is totally unscientific, but I found that my conversations with Melissa and Chad had a comfortable quality that I don’t often get with people I talk to daily here. I also noticed that if a British person cut one of them, or me, off to ask a closed-ended question, it was answered briefly, then there was a pause while the American attempted to gauge whether it was appropriate to go back to the line of discussion they were pursuing before being interrupted, and to give the interruptor the opportunity to add to their comments. Anyway, that’s how I interpreted it.

All this to say: there are lots of conversational differences here, and I feel like I am learning. After eight years of living in the UK, I feel like I am learning. And I am grateful to Melissa for not screaming at me 26 years ago, and for visiting, so that I could think about all of this in way too much detail.

There is a paragraph at the beginning of Team of Rivals about Abraham Lincoln that made me think that reading was not a silly pursuit, that it is worth while, that I am not reading too much. Last month, Robert Caro gave me the confidence that I COULD read, and DKG gave me the confidence that it could be a worthwhile use of time:

Books became his academy, his college. The printed word united his mind with the great minds of generations past. Relatives and neighbors recalled that he scoured the countryside for books and read every volume “he could lay his hands on.” At a time when ownership of books remained “a luxury for those Americans, living outside the purview of the middle-class,” gaining access to reading material proved difficult. When Lincoln obtained copies of the King James Bible, John Bunyan’s Pilgrims Progress, Aesop’s Fables, and William Scott’s Lessons in Elocution, he could not contain his excitement. Holding Pilgrim’s Progress in his hands, “his eyes sparkled, and that day he could not eat, and that night he could not sleep.”

When printing was first invented, Lincoln would later write, “the great mass of men… were utterly unconscious, that their conditions, or their minds were capable of improvement.” To liberate “the mind from this false and under estimate of itself, is the great task which printing came into the world to perform.”

I often feel as if all of the reading I do keeps me from doing, from acting. I need to remember that reading IS doing – that it performs half of that ancient Chinese proverb that Sunny kept telling me, “Savage the body and civilize the mind.”

The summer when I was 19, I was living in Washington, DC, interning and getting paid nothing. No charities existed to help me go out with my friends; I think I had $500 for the three months I was there, maybe a bit more to cover rent. I lived in a studio apartment with my friend from high school, Nate Nanzer; he slept on the sofa, which I think was left over from a previous tenant, and I slept on a sheet on the matted carpet next to our salvaged dining room table. Every night I would roll out my sheet, then wrap myself in it against the cold of our overactive air conditioner, and every morning, I would roll it up so we could walk from the room to the kitchen without stepping on it. My meals every day were either stir-fry over rice or fried eggplant with onions, garlic, and tomatoes, all of the ingredients purchased in the Safeway grocery store at the bottom of the Watergate Hotel. If I was making eggplant, then early in the morning I would skateboard from our apartment near the Lincoln Memorial to the Au Bon Pain up the street, buy a fresh baguette, and skate back, holding it like a football, dodging the potholes and taxis. I had friends in the city – kids I knew from Harvard Model United Nations, from the College Democrats, from Claremont, and I knew Nate, and the other interns in the office, but even with them in town, I only had $500 for the summer, and it was a lonely existence. Washington, DC in 1999 is a terrible place to be young and cashless.

After paying for rent and groceries, I didn’t have enough to go out with my friends.

I was wandering the streets late on a Saturday night in Georgetown, past the bars and restaurants and the riverside clubs, the East Coast prep school kids in their J. Crew and Abercrombie pastels, the laughter from the institutionally powerful spilling out of the doors. Suddenly a quiet spot emerged – a book shop, with standing displays of Dover Thrift Editions advertised for a dollar each. I started browsing, and came away with two books that I stretched my budget for: The Waste Land (and other poems) by Eliot, which I figured might help me get a better sense of what it would be like as an American in Britain when I went to Wales for the autumn semester, and Ben Franklin’s autobiography. I liked The Waste Land and Prufrock, even if they didn’t perform the task I hoped for; my teenage marginalia is painful to read now, but I had good intentions. As for Franklin, he was perfect to read while poor, in DC, at 19. One thing that I read and which helped settle my mind about my summer diet immensely: he endeavored to not remember the food he ate by the end of the meal. As I recall it now, he wanted food to perform a function, and to satisfy his body while he did other good things. This, to me, struck me as a reasonable goal. Stop tasting! Stop enjoying! Just eat to fuel.

(The only other two things I bought that summer that I remember: Shoyeido incense purchased from the Sackler Gallery, which I still have to this day – four boxes from the Jewel series. Shoyeido incense used to have a paper insert describing the difference between their incense and the incense we generally get in the West with a stick in it; they wrote that their incense improved with age, like a truly fine wine. After first reading that, I decided to use it sparingly, aging it to improve it. After a few years, though, I became possessive – I didn’t want to burn it for normal, daily incense, and when a special event came along – buying my first house, getting married, moving to the UK, the birth of my children – I thought: is this really special enough for me to burn this incense? And now, these boxes are 24 years old, stored in an even older cigar box, and I constantly think: I should burn this, but now it is too special, too much a part of my life, of the many moves around the world, of my story, to sacrifice like that. I am sure Kahneman has written about this. Associated-Experiential Value, or something like that.

I also bought a bottle of Omas ink from a pen shop in Georgetown, in August, just before I left. In retrospect, buying books, fountain pen ink, and fine incense, I had my priorities right back then.)

I was reminded of Franklin’s approach this month. Lex came back from a visit to Brazil, and brought me two bags of coffee. He said that they were not very good, as they were the coffees that were sold in Brazil; the really good stuff was set aside for export, like tea in Sri Lanka. I thought of John Johnson, teaching me to taste, and of drinking wine with Tom, and all of the tasting parties with Knut. The bags had tasting notes in Portuguese – I recognised some of the words because of their similaritiy to Spanish and French, and determined that the drinker was supposed to taste raspberries and chocolate.

I opened the first bag, and made the first cup. I didn’t get raspberries and chocolate. Instead, I tasted a roadside stand, with dirty white tents branded with Brazilian beer logos. I tasted broken concrete under my sandals, and white plastic tables and chairs in partial shade, and oft-washed mugs, a few with chips, a few with non-fatal cracks stained brown. There was a grill with meat, and, just behind the tents, dark green, and birds. And heat, the heat that comes with winged insects rubbing their legs together to find a mate, that doesn’t have a breeze, the heat of a yellow-white sun.

I messaged Lex about it. In the ensuing conversation, I realized that I had moved away from Franklin and Johnson and onto something new to me. Instead of tasting terroir, like the chalk in the soil from a wine, I want to taste stories, memories, scenes. In rum, I don’t want to taste the molasses, or the sherry in the aging casks; I want to feel the sharpness of the cane leaves, see the way the plants crowd the dirt roads, smell the burning at the end of the harvest. In Spanish wine, I want the house red that you get little glasses of at El Bochinche, or Bar Tomas, so that I can feel the metal edges of the table making indentations in my forearms, and hear the waiters complaining with patrons about the construction outside and the politicians who thought it was a good idea, and see the smile of the two old women sitting near the window, with gold bracelets and loose silk shirts, sharing coffee and quiet secrets.

The end of the thought process, sparked by this coffee, was this: terroir is what people have when their imaginations, or memories, are not enough to let them see what they taste.

“Men work in an office, women work at home.”

Daniel didn’t mean that women do housework; it is 2023, after all. His experience, though, is that daddy works all day, often at the office, and mommy works a good portion of the day, and then at night, at her computer at home. I had to explain to him that women work in offices, too, and that I work at home, so why did he think otherwise? And he agreed.

He hugs me now, maybe once a day, sometimes in public, and when I ask for a hug. He kisses me goodbye, and goodnight, with real kid kisses – an upward tilt of the head, pursed little lips, a smacking sound that is often made after I have pulled away.

And he takes care of Nick, even though there is a real sibling rivalry developing. He loves Nick, and Nick looks up to Daniel, but Daniel knows that there is competition for our attention, and that sometimes Nick has to win because he is too small to do things on his own. I am trying to make sure that Daniel knows we love him, and to reassure him that he has a special place in our family that will never be taken away from him.

And Nick – suddenly, he is walking, taking fat-thighed, lumbering steps, grinning the whole way. He is the smiliest baby, and far, far more cuddly than Daniel ever was; Daniel would push me away whenever I held him facing me, but Nick, more often than not, will hug me with his legs around my torso and his arms on my shoulders and neck and push his face against me and just stay there, as if to reassure me that he loves me.

And the books of May:

- The Earl of Louisiana, A.J. Liebling – a book that must have been very much of its time. It came highly recommended to me, but I don’t understand enough about the subject to have it be meaningful.

- The Netanyahus, Joshua Cohen – absolutely stellar. Cohen creates such an incredibly small, claustrophobic world, and goes so deeply into the lives of the characters, and creates what it says on the cover: “An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family.” Very much worth reading.

- Strong Female Character, Fern Brady. I remember reading Why Did You Stay? and being really interested in the inside life of Humphries; I think I hoped that this would be similar. It wasn’t. The first few chapters read like a standup routine, which I am not opposed to – A Horse Walks Into A Bar was one of the funniest, saddest, most beautiful and painful things I have ever read. In Brady’s hands, though, it was not literature. Then it got into the implications of her lack of diagnosis as someone with autism, and I started to really empathize with her. Recommended…warmly.

- The Red Queen, Matt Ridley. Terrible.

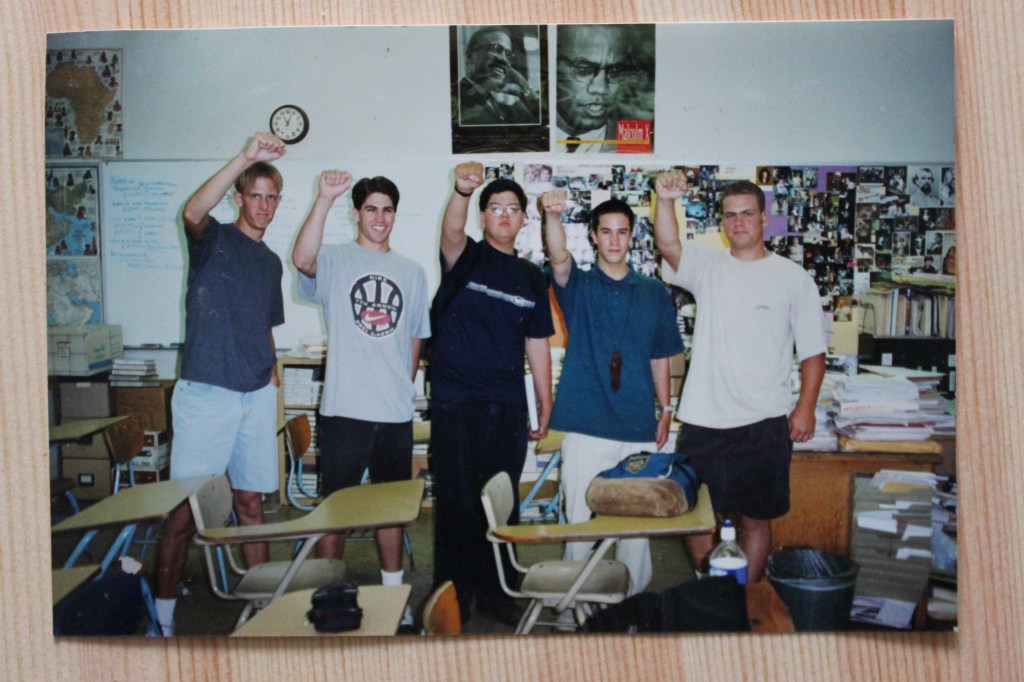

- Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Manning Marable. This was a bit of a revelation for me; I had read it before, and liked it. Reading it so closely after Caro’s LBJ books, though, I had the thought that perhaps all major figures – I hesitate to call them “great people” – go through reinventions, through changes. There is a temptation to go through life with an attitude that we are made in a particular way and should not deviate from that – my mother felt that way, and she criticized Dale Carnegie and How To Win Friends And Influence People because she said it made people fake and insincere. I always felt that we could change, and should change. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention reinforced my belief that change not only can occur, it can be self-directed, and radical changes can happen over time, and change is necessary for greatness.

Reading about Malcolm X, I was inspired to listen to his speeches again. I first learned about him in high school, from Mr. Kraszewski, and then I started listening to him in college. Bianca would sometimes come by and I would be listening to The Ballot or the Bullet, or Message to the Grassroots, and we would talk with X’s voice as our backdrop, so much that it became an expectation, an accepted part of our interactions. I listened to him so much that I memorized entire large portions of his speeches, and tried to get the rhythm right, trying to use pauses and stutters like he did.

I have a few proud moments in my life, ones that stand out as high-water marks, and this led to one of them. In the middle of the Cash Mobs thing, Fox Money, the Rupert Murdoch-owned beast, emailed me and asked if they could interview me on live, national TV. Like that moment at President Massey’s house, I said yes, absolutely, and knew exactly what I was going to do.

The interview was not only cordial, it was enthusiastic. I hope it exists somewhere. I really liked talking to them; I liked talking to all media, but Fox Money was unusually nice, probably because I was supporting small business and capitalism and it was a feel-good story for the eaters of raw meat. Reporters ask a lot of the same questions, though, so when they asked me why people should start or join Cash Mobs in their communities, I was ready. I don’t have the exact transcript, but it was, approximately,

The economic philosophy of Cash Mobs means that we have to educate people into the importance of knowing that when you spend your dollar out of the community in which you live, the community in which you spend your money becomes richer and richer, and the community out of which you take your money becomes poorer and poorer. We want to show people the importance of setting up these little stores and developing them and expanding them into larger operations. Wal-Mart didn’t start out big like they are today; they started out with a dime store, and expanded and expanded and expanded until today they are all over the country and all over the world and they getting some of everybody’s money. Amazon, the same way. It didn’t start out like it is. It started out just a little rat-race type operation. And it expanded and it expanded until today it’s where it is right now. And you and I have to make a start. And the best place to start is right in the community where we live.

Bianca was eating breakfast at a hotel in Austin, Texas, when she looked up at the television and saw me on the screen, then emailed me. I suspect, or maybe am overly hopeful, that this was the interview she saw, and I am willing to bet money that if it was, she was the only person who realized that I was using the economic philosophy of Black Nationalism, as espoused by Malcolm X in his speech The Ballot or the Bullet, almost verbatim, in as close to the original cadence as I could muster, to justify myself and my movement, and I was saying it on the most conservative news channel in the country, and getting the hosts to tell me that they agreed with me completely, and hoped that I would be successful, and that America needed more young people like me, and that when I thanked them with that big, shit-eating grin, I meant it sincerely.

As I write this, a letter from Ryan in Texas sits in my portfolio, and I mean to send a letter, as well as assorted treats, to John, in Germany. I will get to Ryan’s response this weekend, and John next.

Picture this: it is 2023, and three men, who went to school together in the 1990s but were not actually friends, are hand-writing each other letters and posting them around the world. When I imagine it, I see a globe, darkened, with three points of light connected by tiny yellow-lit strings, and another to Tom in Oakland, another to Bianca in Chicago, and, the more I think about it, the more the world lights up, thousands of points linked together, and it is up to each point to reinforce the connection so that it keeps glowing. Jojo, in Portland, would have liked that image; I should write her.

I only wish I still had that bottle of Omas ink.

Happy Father’s Day Andrew! You are such a good dad—clearly the source of your greatest pride. Hardly surprising as you are such a good friend, too. I love the strings of light. Your stories about your friends are really vivid too. They come alive to me in a way that is a gift. And I can’t get enough pictures of the boys! Letter is enroute but enjoy the day and love to Alice.

LikeLike