When I got to Pitzer, one of my first classes was Asian-American Literature. It was taught by a new professor, and I think she had six or seven students – me (a hapa), four or five full Asian-Americans, and one white guy who always seemed like he was there to fill a graduation requirement. We covered a lot of the twentieth-century AA canon, from a memoir of a great-great-grandson of Chinese railroad workers to the Japanese-American internment to a book about being Korean in the 1980s that was remarkable only for its lack of anything interesting to say.

My most enduring memory of the course was waiting with everyone else, one particularly sunny day, for the professor to show up. All semester, nobody said much outside of answering her questions, and I don’t think I knew any of their names. We were in a Scott Hall classroom, the sun was streaming in, nobody had cell phones or laptops back then, and the only sound was the air conditioning until one of the women said, “Can I ask you guys something?” and proceeded to say that they didn’t understand the point of Asian-American literature, as it was all about feeling like outsiders in bygone eras, while we were all at $30,000+ per year colleges, and part of the inner establishment, and it was like an immense weight was lifted off of each of our shoulders. For what seemed like fifteen minutes, all of us – except maybe the white guy – bonded over our shared privilege and relative lives of ease, and how maybe these books would be interesting to our parents or grandparents, but for us, American society was wide open, and our experiences were completely foreign…or, perhaps, “native” would be the better term. The professor was used to walking into a classroom of silence; when she walked in that day, we were suddenly all chattering and laughing and friendly, and the look of confusion on her face was priceless. And she suddenly couldn’t contain us – for the rest of the semester, we challenged her, the texts, and each other, in a way that would have made most teachers overjoyed, but, as we were collectively critical of the AA experience that was being portrayed, and which she had studied for her Ph.D. at Harvard or Yale or Princeton, must have been difficult for her to process. In retrospect, that was the beginning of my Pitzer education – the fact that instead of passively accepting whatever was presented in class, we demanded that the text answer to our sensibilities and made it justify its worth. I don’t remember the woman’s name who started that conversation, but I am immensely grateful to her.

So for 27 years, I ignored Asian-American literature.

Then I read Stay True.

Alice got it for me for Christmas, and within the first three pages, I was prepared to name it the best book I had read in 2024. Recently, I was talking with my friend Charlie about When We Cease To Understand The World; I mentioned that throughout the entire book, I felt as if there was a low, slow, ominous drumbeat constantly pounding away. In Stay True, the sensation was more of the warm 1990s California sun hitting my face, with the low chatter of waves in the background, and young people chasing frisbees in their swimsuits, even if it is a cool 60 degrees with a light wind coming off of the Pacific. Hsu, a Chinese-American from California, was born two years before me; his best friend Ken, who is the subject of the book, was from El Cajon, and graduated from my rival high school in 1995. The book addresses race in America as a “third” category outside of the black/white dichotomy, but also addresses music, writing, the 1990s, California’s place in America, friendship, memory, life souvenirs, and a hundred other points in a wise, considered, subtle and penetrating way. There were dozens of sentences that made me breathe in sharply and nod; there wer pages where I was almost angry that he had stolen one of my private memories; there is a line about the Spice Girls movie that made me laugh for fifteen minutes, despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that it is in the middle of a section about Ken being executed in an alley by some carjackers. I am going to get a subscription to the New Yorker just to read what Hsu has written; if this is the future of Asian-American literature, I hope that Daniel and Nick take a course with it on the syllabus, as…well, in many ways, I feel as if he has written about my youth, and won a Pulitzer for it, and I would like them to read it and think to themselves, “this is what dad went through. Cool.”

Unrelated to books, but to education: we went through school assessments for Daniel. It was a frought, terrifying process; first, to have one’s first child be evaluated for their mental, social, and perhaps physical fitness to join elite private schools, and second, because there are so many differences in terminology and education between what I grew up with and what Alice grew up with (at boarding schools in England) and what Daniel and Nick will experience in the Scottish system. On two occasions, we took him to a school, watched him disappear with a group of other four-year-olds, and then were surprised when he came back first from the group, far before the other students.

And on both occasions, he apparently shined. It is impossible to know what he went through – he won’t say anything other than he has forgotten what the assessments were like – but he was accepted to both the schools, and is going to our collective first choice. It is incredibly strange, after a public school education in East County, San Diego, to think that at least one of my sons will be wearing wool shorts and knee-high socks and a tie and jacket with a coat of arms in order to go to kindergarten, and might be on track, without any concerted planning or effort, for Oxford, or Cambridge, or the Ivy League. What if he got into Harvard, or Princeton? I’d be happy, of course, but part of me hopes that he is really lucky and works hard and really wants a good education, and that he gets into Pitzer.

Just after Stay True, I reviewed my bookshelf for priorities. We don’t have much time before we go to Italy, so I wanted to pick out hard-back books to read, as I will be pounding through Kindle books for a few months; one of the hardback books that called to me was Fewer, Better Things. If there is a manifesto that better describes a healthy relationship to the world of objects, I would love to see it; until that moment, though, this is one of the best descriptions of a material lifestyle I have ever come across. Instead of promoting Hermes-worship, or asceticism, Adamson points out that objects are central to the way we experience the world, and, accepting that, proposes healthy ideas about how to go about experiencing the material universe. He explains why a vintage photo frame is generally more satisfying than a new one from Ikea, or a hand-made leather belt is a better option (all-around) than a pleather one from WalMart; he also describes what could best be thought of as a healthy meditation on the material world around us, and why we should stop buying crap. There are many obvious ideas, but just because they are obvious doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be made explicit; this is a wonderful way to re-connect with the world around us. He also addressed the idea of “souvenirs” that made me smile – I generally frown on the idea of buying a snow globe paperweight from Aspen, or a fridge magnet from Venice, or a sweatshirt from the Outer Banks, but I now have more sympathy towards the kinds of people who would buy these things.

January and February saw other books that merit brief mention:

- Glucose Revolution – there is apparently some controversy around this book, as it was written by a tech worker in a breathless “you’d never believe what these scientific studies say!” sense (a bit like James Nestor, but without the storytelling skill). I ignored all of the “this is the science” chapters, as…well, it isn’t that I don’t care, but I wanted to see what she recommended. In the end, there is very little that is objectionable about the core takeaways; nobody will die from eating more broccoli and spinach, drinking a spoon of vinegar in water, or cutting out some sugar and carbs in the morning in favor of something like a salad. It isn’t an amazing book, but I think there is some solid advice, and if it gets people to be healthier, then it is doing a good job.

- The Art of Clear Thinking: A Fighter Pilot’s Guide to Making Tough Decisions. The core takeaway: ACE, or assess the situation, choose a response, and execute that response. Plus a lot of good stories.

- Naples ‘44 – I tried to read a bunch of books in preparation for Italy – a book on Rome by Mary Beard, which I found absolutely terrible despite (or perhaps because of) her reputation; a book on Roman emperors, which skipped around too much to make sense; and one on the mafia, which probably made sense to Italians who understood the references, but didn’t really capture my attention. This…well, it did. It is a series of journal entries by a British intelligence officer about his time in Naples and its surrounding villages; he captures the desperation in the people, the impact of war, the confusion and strange social positioning of invading soldiers, the characters that existed, and the poetic beauty of the street life of Naples in 1943 and 1944. I can’t wait to actually see some of the places he described, knowing what happened there.

When I was in college, a girl I knew was studying abroad in Australia. I don’t know why this story stuck with me, but when she got there, and started meeting people, every Australian she talked to ribbed her a bit about the swimming results. When she had no idea what they were talking about, they were at first shocked, then just assumed she was ignorant; some sort of world championship had just taken place, and Australia had beaten its long-time rivals, the United States, for first place, in an upset that, to Australian minds, must have made every American both red from rage and green from envy. Didn’t she follow swimming? No, she didn’t; she didn’t even follow baseball, or football, or the stock market in the 1990s, much less world swim meets. Quickly, though, she came to the conclusion that Australians – or, at least, the ones she met in every bar and classroom in Brisbane – were so obsessed by swimming championships because it was…well, one of the few things that they shined in on an international stage, and so they projected their obsession with the standings onto everyone else, particularly their arch-rivals across the Pacific. It is a bit like how, maybe once a year, a British person gets the nerve up to ask me what I think about Canada. My response: it is a nice place, I really liked going to Toronto and Montreal, I hear Vancouver is wonderful, I would love to see some of the mountains sometime. But, they ask, don’t I hate the Canadians? No, I say, why would I? Because, of course, Canadians always get riled up when they are mistaken for Americans, and seem to resent their southern neighbor; isn’t it reciprocated? I always think of Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: he argues that it is impossible, psychologically, to hate anyone who we think is inferior to ourselves. In order to hate, we have to respect something about the other person, or at least have an inkling that they are better than us in some way; otherwise, we can’t hate, we can only pity. As Americans, we don’t generally hate Canada, and I doubt we resented the Australian dominance in the 1000m butterfly; we generally ignore the small things and, instead, focus on bigger geopolitical issues (or, at least, I like to hope we do).

Anyway: I thought of this when Sunny said he was going to Senegal. Senegal…what is their equivalent? What do they take pride in – perhaps “irrational” pride in? Who do they see as their rivals, in West African and around the world? What do they assume everyone else in the world knows about Senegal? Who in Senegal – politicians, musicians, local businesspeople – do they assume we would have heard of? What famous Senegalese dish must we have tried at some point? I thought that it would be an excellent exercise for Sunny to go through on his trip…

And more broadly, perhaps. What do people in Edinburgh assume that the rest of the world knows? Who are the rivals in Scotland? What sports should be on everyone’s radar? Even more specific: when I meet someone tomorrow, what should I wonder about their own prejudices and projections? What are their obsessions and thumbscrews? I feel as if this would be a very useful exercise, both for travelling as well as in my daily life.

First, we tried to get Daniel into knock knock jokes. It worked, to an extent – he still doesn’t quite get some complicated ones (Alice who? Alice fair in love and war…) but he loved “interrupting cow.” We did that, and interrupting chicken, interrupting dog, interrupting sheep, and then one day he walked up to me and said,

Daniel: Knock knock.

Me: Who’s there?

Daniel: Interrupting nothing.

Me: Interrupting nothing who?

Daniel: (stares into my eyes).

He often impresses me, but this was on a whole new level.

Nick, for his part, started with this:

Nick: Knock knock.

Me: Who’s there?

Nick: Cow.

Me: Cow who?

Nick: MOO!

As he is a year old, that was pretty damn impressive, in my opinion. But then, one day on the tram, he added “chicken” to the joke, and bock-bocked his way to a good laugh. The next day, he added sheep, and then a few minutes later, duck. It is obviously basic, and elementary, but I could watch his brain trying to master this new skill, and he is making connections between things that simply blow my mind.

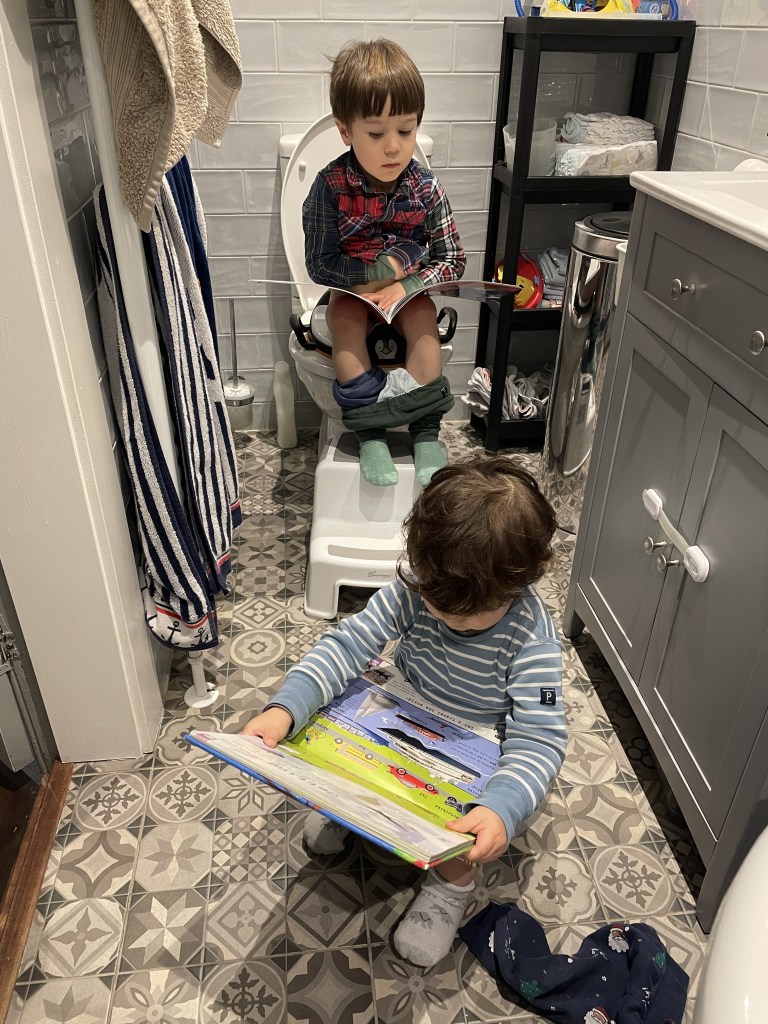

Also: he can poo on a potty sometimes, which is arguably more important.

Other Daniel milestones:

- He was asked to move up a level in Judo. The teacher just came up to me and said, “He is way too good for this class.” A few weeks later, he said to me, “Daddy…I don’t think I am doing enough judo.” Twist my arm.

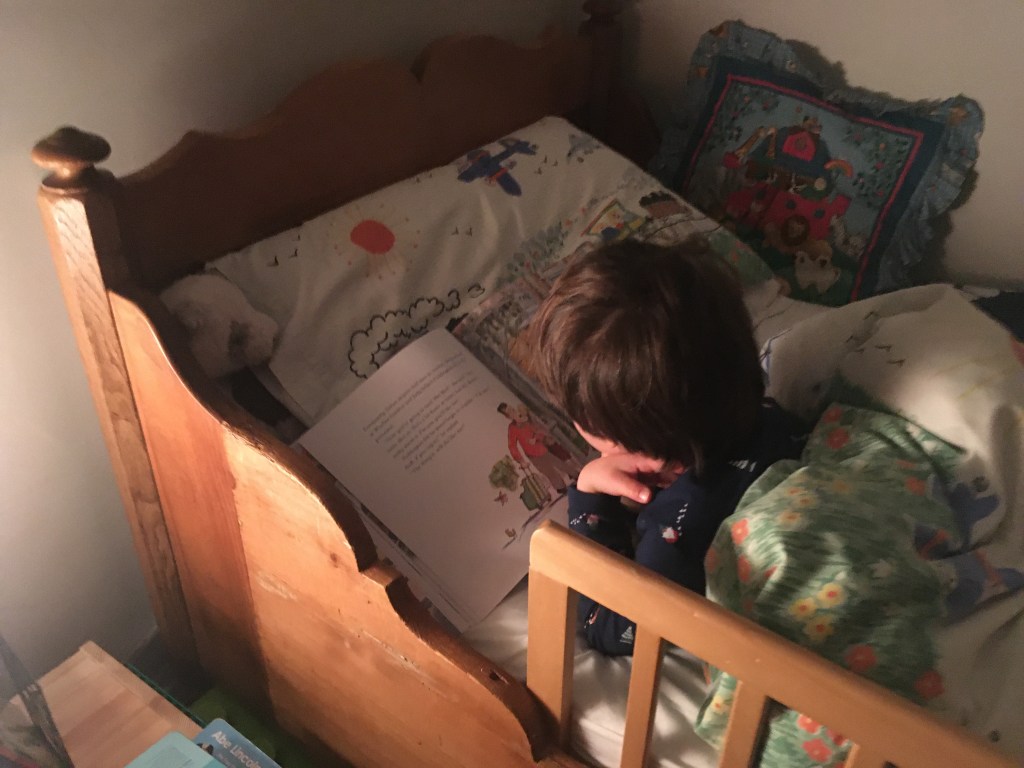

- Regularly, I walk into his room in the morning to find out what he wants for breakfast, and he is reading in bed – sounding out words, looking for patterns, exposing his mind to new worlds. My heart jumps every time.

- He uses “poo” like people use “shit”. For example, when watching rugby, he will shout, “Go Scotland! You win that poo!” If he likes something, or thinks it is funny, he will say, “That’s the poo!” or “That’s some goooooood poo.” If he doesn’t like something, he will say, “That’s poopy.” He knows the word “shit,” but Alice doesn’t want him using it, so he has changed; it is amazing, to me, that he can pick up on uses and variations and substitutions at such a young age, and knows that he can get away with “poo” in its place.

- He loves Calvin and Hobbes. Perhaps my greatest daily joy is reading him a new panel and him falling over laughing by something that I, too, think is brilliantly hilarious.

- They pick up on habits from their parents; besides reading in bed, both Daniel and Nick now often insist on going out with either bow ties or neck ties on, and they request aftershave, and brush their shoes. They also have personal shoehorns hanging off of hooks in their closet, which they use for putting on their shoes. There is a snowball’s chance in hell that I would deny them any of these.

Sunny asked if Daniel or Nick displayed any habits or traits that they may have inherited from us. With Daniel, it is too hard to determine if he reads in bed because he sees us doing it, or we reward him reading with positive reinforcement, or if it is a genetic predisposition; with Nick, the thing that comes out most strongly is his generosity, which I assume he got from Alice. He will ask for a drink, take a sip, then insist that someone else have some – “Daddy! Water! Daddy! Water!!!” or will try to get us to try his rice. When out, he will pack two hand shovels and, when it is digging time, he will get them out – one for him, one for me, so that we can both dig. If he picks up a stick, it is only a few seconds before he is looking for another one, and will hand it to me, saying “Daddy stick!” so I know I need to play with it. It isn’t one of those things I think we model; there is an old photo of Alice shoving a french fry into her grandfather’s mouth after she caught him pretend-stealing a fry and thought he might be hungry. My opinion: nature AND nurture, and we have to pay attention to both.

And that is something I want to focus on.

I will risk sounding like an old raver shaking her cane to note that subcultures, even the vapid ones, used to tie their participants to people and places. Getting into a scene could be work; it required figuring out whom to talk to, or where to go, and maybe hanging awkwardly around a record store or nightclub or street corner until you got scooped up by whatever was happening. But at its deepest, a subculture could allow a given club kid, headbanger or punk to live in a communal container from the moment she woke up to the moment she went to bed. If you were, say, a suburban California skate rat in 1990, skating affected almost everything you did: how you spoke, the way you dressed, the people you hung out with, the places you went, the issues you cared about, the shape of your very body. And while that might not have seemed a promising plan for teenage well-being at the time, by today’s standards of diffuse loneliness and alienation among youth, it looks like a very good recipe indeed — precisely the kind of real-world cultural community that has been replaced by an algorithmic fluidity in which nothing hangs around long enough to grow roots. Kids are not failing by wanting to be cottagecore or meatcore or this new preppy. It’s the culture available to them that is failing, by no longer being able to connect any of these categories with lived experience or social meaning. Kids, in all their blowzy creativity — the same creativity that invented movements from Romanticism to hippiedom to hip-hop — need more, deserve more. It’s hard to think otherwise when looking at the Aesthetics Wiki entry for Peoplehood, “an aesthetic revolving around common acts of kindness and intimacy that are present in daily life.” It might be time to start thinking of 20th-century parents’ problems as solutions: The youth belong at the rave, at the block party, in the mosh pit, loitering in the park at midnight.” – Mireille Silcoff, New York Times

Damn right – or, as Daniel might say, “that is the poo.”

Bow ties, apple slices and poo. That covers it. 👏

LikeLike