My friend Alex sent me this message: “Used to read your blog for the book recommendations (and your interesting stories) – now I’m all about your parenting tips.”

One thing that I always tried to avoid was unsolicited parenting advice. New parents get tons of it; we heard everything from “now is the time to start saving and investing for their futures” to “you have to hit them sometimes.” (Note: we follow the former, and do not follow the latter.) I hate unsolicited advice anyway, and much of the advice people seemed to want to give was inane or offensive, so, rather than ever be accused of doing the same, I just avoided it entirely. Parents have enough to think about without filtering out nonsense.

But Alex a new mom, and…well, she did send me the above. I won’t offer unsolicited parenting advice, but I am happy to write down a few ideas she might be interested in.

- Show them love. In Triumphs of Experience, a summary of the Harvard Grant Study, this was the most important thing of all for raising good kids. If a child feels loved, particularly from the father, then they will likely turn out just fine.

- Don’t bribe them; just give them intermittent and unpredictable rewards. This came from the work BJ Fogg and Nir Eyal do at Stanford; a predictable benefit from good deeds leads to transactional behavior, where people expect to get a reward if they do something. This takes away the “being good for its own sake” mentality. Bribing kids is terrible; however, giving unpredictable rewards helps reinforce behavior.

- Give the dog a good name. Whenever a parent insults their child, especially to someone else, I watch the kid’s face; it is heartbreaking. Don’t discourage them, especially in front of other people. Your kid is on your team; build them, coach them, give them a good name to live up to.

- Incentivize the behavior you want. This is different than bribing. Recently, Alice reminded me of a time that she had organized a play date for Daniel; the parents came over with their kid, who was a nightmare. They seemed to have filled him with donuts before he got there, and juice while he was here, so his blood sugar was all over the place. At one point, the father said to the child, “If you stop kicking me, I will buy you ice cream.” It was at that point that I thought: I don’t want Daniel hanging around this kid or his parents.

- Model and normalize the behavior you want. This was from my friend Mike Pastor. Never get in a position where you have to say, “Do as I say, not as I do.” Do better than that. Be better than that.

- Answer questions. When kids ask questions, they are trying to understand something. Don’t brush these questions aside. Answer them as truthfully and honestly as possible, even if it is a question that they have asked a hundred times before. If you can’t bear repeating yourself for the thousandth time, ask something like: “What do YOU think the answer is?” Then, continue to engage.

- Don’t lie. I take this to an extreme; sometimes, Daniel will say something about Santa Claus, and before I can tell him it is just a story, he will say, “Don’t worry, Daddy, I am just pretending.” But I think it is important to build trust with kids; lying is a great way to break that trust. If you are going to lie about Santa Claus, or the Tooth Fairy, or the Easter Bunny, look in the mirror and say, “I am intentionally lying to my child, and I understand that this will set a standard of conduct with them.” Also, if you are willing to do that, also read the story of the boy who cried wolf to them.

- Let your no be no. I see this as an extension of “don’t lie.” If you say no to something, let it mean no. If a kid hears no, and whines, and gets a yes, then you are training them to always whine when you say no; they won’t know when your “no” means “yes,” and will keep testing that, and not trusting you. One thing I do with Daniel, though, and hope to do with Nick: if Daniel asks me why I say no, and I explain it (point six), and he challenges some of my presuppositions, and he is right, I will reverse course and be clear that I was wrong, and how I was wrong, and thank him for clearing things up. However, just whining will not change my mind. Logic, reason, and fact? Yes. Point five.

- Reason with them/give them reasons. Kids can understand a lot; “because I said so” is not a good way to build trust. Tell them why, and teach them how to understand the world.

- “Are you ok?” is better than “You are ok!” This one was from Alice. I see kids falling a lot, then crying, and their parents saying, “You are ok!” We say, “Are you ok?” If they are, then they just bounce up; if not, they will cry. I’m surprised at how often Nick takes a hard fall, gets up, and doesn’t make a big deal out of it because, I suspect, we give him the opportunity to be ok.

- Sit with their pain. A follow-up from 10. Sometimes a kid is hurt. Help them through that. Most of the time, it just means holding them.

- “I can’t let you do that.” Another one from Alice; rather than stop them from doing things, tell them, “I can’t let you do that.” (Note to self: I really need to start doing this more with Nick.)

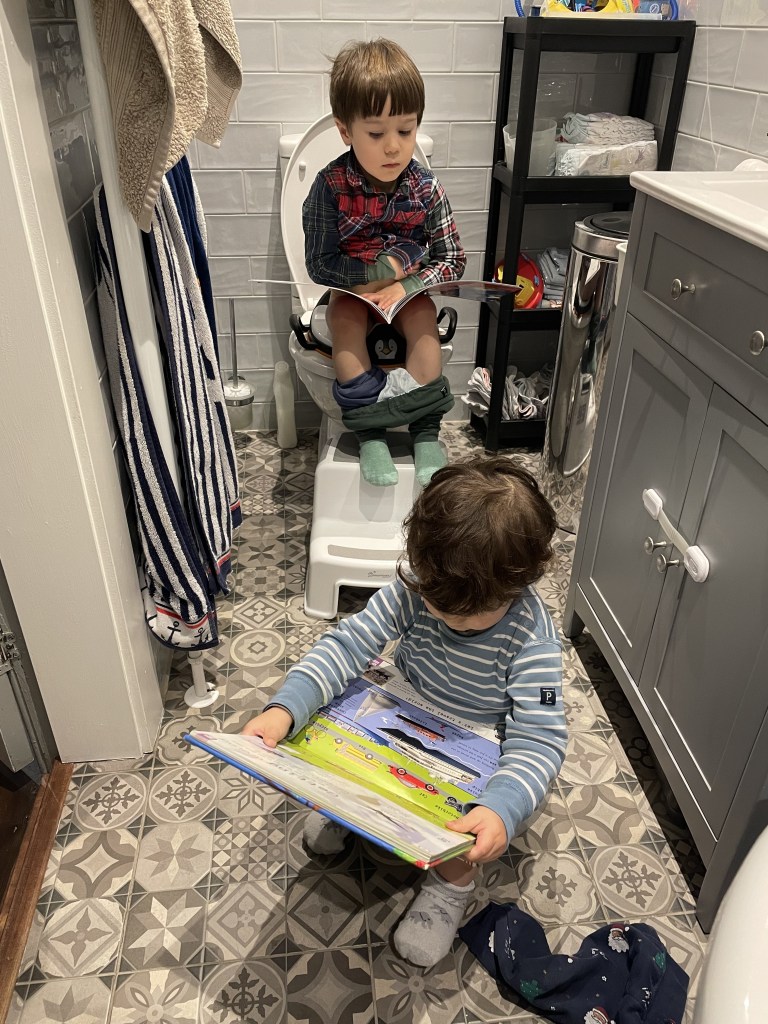

- Stop reading bad books. Just after Daniel was born, a father we knew was talking about how much he loathed Pip and Posy books, but his daughter loved them. He then said something like, “I know we are not supposed to pass judgment on their books, and just read them so they get into reading, but,” and he grimaced. To me, this idea is total male cow manure. There are not only bad books for kids, there are a number of them that are actively harmful. In Fireman Sam, for example, the main child character keeps causing disasters, including fires, and barely receives a verbal reprimand; in many cases, the adults actively encourage him. If you are trying to create an incredibly negative role model, you could do worse than Norman Price. There is one where Norman steals a boat, goes out in floodwater, and almost drowns; the adults tell him he shouldn’t have done it, but he was very brave for going out to try to save a sheep. In that circumstance, is a kid – who we try to encourage bravery in, whether it is going across a balance beam, using a hand dryer, or petting a dog – going to think that bravery was a bad thing in a situation where this kid almost drowns? The messages that these books reinforce are terrible, and there are plenty of amazing books that kids can read, so I just say no, and Daniel now knows that I don’t read Fireman Sam, Pip and Posy, Peppa Pig, and, often, Thomas the Tank Engine. The idea that there are no bad books for kids is absurd; there are, and it is your job, as parent, to ensure that they have good ones.

- It’s all about the number and volume of words that they hear. I think this came from a book about brain development from about ten years ago: basically, the idea is that every new word a child hears when little is a word they will be able to use in the future. Children’s synapses form in massive numbers; then, there is a culling in the braid of weak synapses, and then synapses can form again. We go through many of these synapse culls throughout life. The early ones are critical, though, as the more synapses form, the more will exist after the culls. The best thing: get them hearing words. With Daniel, we made it through a large number of Shakespeare’s works, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and countless other works, as well as extensive music (Hamilton! Biggie! Tupac!) all to help synapses form; he’s gone through at least one cull, but I think we have set him up well for the future.

- Eat your vegetables. Daniel currently requests eggs with onions and spinach for breakfast, and, if I make a ribollita, he will eat all of the cavolo nero out of it. I have to believe that this is because he sees me eating it.

There may be more things I think of. Anyway, if I were offering unsolicited parenting advice, this would be the start of it.

Alex: your daughter is beautiful, and you are an amazing mother!