When I was little, one of the greatest things we could do in a day was go to Parkway Plaza. I’m sure it served the same function that playgrounds serve me now: it was probably an easy place for my parents to take us when they wanted to get out of the house, and we could walk around and be somewhat safe. There was a Tower Records, which I think of whenever I read the Dark Tower series by Stephen King, and a Hot Dog On A Stick, a Panda Inn, a Cinnabon, a PayLess Shoes, and, absolutely most importantly, a KayBee Toy Store. Even though it was smaller than the Toys-R-Us that was in the next town over, near the fancier Grossmont Center, KayBee was more magical for me because it always had a big display container full of books near the cash registers, and Toys-R-Us had…well, it only had toys. In my memory, these books were a dollar each, and they were all from a series of abridged, illustrated versions of classics that some genius had put together, and my mother was always happy to get them for us. I still have the copy of Tom Sawyer that, when I was five or six years old, was the first book I ever read in a single day; I can still remember how excited and proud I was back then, running to tell my mom that I had finished it in the middle of the afternoon. Imagine reading a book in a single day as a kid! Actually, imagine finishing a book in one day now. The dream! I think we had ten or twenty of these titles, and I read them over and over again – books like Treasure Island, The Count of Monte Cristo, Huckleberry Finn, A Tale of Two Cities (which, let’s be honest, could have done with some abridging).

From these books, particularly the Mark Twain ones, I got it in my head that India Ink was the most incredible ink in the world. I had no idea what it was, and, writing this sentence, still have no idea how it is different from any other ink, and I don’t want to google it – I want to keep the mystery alive. India Ink, though – just the sound of those two words makes it seem indelible, exotic, historic. Did the British invaders use it when keeping records in the subcontinent? Did they bring it back from India because it was superior to Continental inks?

One weekend, our neighbors across the street had a yard sale, and I saw a bottle of ink that they were getting rid of. I may have paid a dollar for it, and my dad, who saw me trying to figure out how to use it, decided to give me his fountain pen so I could actually write something with it. That was the beginning of a lifelong love; after that, I almost always had a fountain pen in my desk, and often in my pocket. However, I never paid much attention to the ink. To me, after I was seven or eight, ink was all more or less the same, and as long as it was blue, I was happy.

When I got to Pitzer, I took my pens with me, and luckily, my suitemate Alex shared this interest – we both had black Cross fountain pens with pistons full of Parker ink that we got at the Office Depot in Upland. With him, I also got into tea, and, without him, Japanese gardens. I am not sure how that happened; perhaps I was at the tea shop and told Mrs. Lee that I preferred Japanese art over Chinese art, and she suggested that I look into Japanese horticulture. Perhaps. However it happened, I started going to the Hannah Carter Japanese Garden once a week, usually on Fridays. It was owned by UCLA, and the public could access it by reservation; back then, there were three parking spaces, so it was usually quiet, and it was absolutely stunning. I went alone at first, then with friends, and then started taking dates there – the glory of the garden was that it constantly changed, so if I didn’t like my date, I could still enjoy the beauty of the plants and the water, beauty that would be different by the following week. Then I got to know the volunteers, which opened up a whole new level of access to me. Daniel, Nick, a bit of fatherly advice: if you are on a date with someone from a small, private liberal arts college, there are worse things than knowing the volunteers at a Japanese garden so well that they tell you the fish are hungry, and that you can help them by getting the bags of fish food out of the big brown bin behind the bamboo, and you then measure it out in the plastic pitcher and show your date how to let the fish eat the round pellets from your palms. There are far, far worse things than that. If your date is not impressed, make sure you shake hands when you say goodbye.

I started getting books out of Honnold Library about Japanese gardens. One thing that stuck with me was the idea that the majority colors in Japanese gardens are green, brown, and black, because those are the most common colors in a natural garden, and against those colors, other colors stand out with more vibrancy; using too much red, or orange, or blue, or any other color, ends up being garish and unnatural. I vowed to try to implement that color rule wherever I lived, down to the picking tan and green sheets, or wall paint, or flatware, or tiles. It became an easy way to make interior design decisions, as well as to make my life seem more peaceful. I hope that someday, you think of the houses that we lived in, and the feeling you get is of having grown up inside of a plant, or a tree – that’s the feeling I aim for.

Before I studied abroad in my junior year, I lived in Washington, DC. There was a pen shop in Georgetown, near the water, that I went in before I left, and they had a bottle of limited edition Omas ink that came in a rounded octagonal bottle that looked like a jewel; the idea was that the user could tilt the bottle and rest it on one of its flat surfaces as the ink was used up, and this design allowed the user to draw the ink into a piston at an optimal angle. I had never heard of Omas, but the genius of the bottle entranced me. Maybe I spent $10 on it, or $20 – a significant portion of the $500 I had for the summer, but worth every penny. I took that bottle to Cardiff, not considering the potential tragedy of it exploding on the plane, and kept it on my windowsill; I can still remember the way the light refracted through the glass on those rare sunny Welsh days, playing with the blues and greens and purples in the ink before it exploded into the room in a thousand directions, and the joy of filling my pen every morning, just like I read Lyndon B. Johnson had made Lady Bird do for him.

I’d chosen to go to Wales because of my first real breakup. I was very dramatic about the whole thing, and decided that the only proper course of action was to get out of America for a year; that would show her. The only way to study abroad for a year as a political science major seemed to be on an EU-focused course; I would start at Cardiff in the autumn, and then either stay for the spring semester or move on to Alicante.

The problem with that plan was the rowing.

Rowing on a crew wasn’t something we saw much of in San Diego in the 1990s; with surfing and sailing, and without rivers, we didn’t see many sculls or eights plying the waters. Again, probably from books, I got the idea that rowing was an elite sport, and one I aspired to enjoy; my rebound from the breakup turned out to be a Boston Brahmin who wholeheartedly approved, so when I got to Cardiff, one of the first things I did was sign up for the rowing team.

I showed up to the first training with 117 other men and maybe 60 women. I didn’t realize how highly regarded rowing was in Britain, or how many young men I would be competing against for a spot in a boat. The good thing was that the dropout rate was rumored to be ludicrously high – the coach of the team said he expected 90% of the team to be gone within a month, leaving just a few people at the end. At our first social night, I spoke to him for a while, and he said that he had a feeling that I would be one of the ones who stuck with it. I remember walking home, drunk, inordinately proud that I gave off that vibe.

Seven of us ended up reliable; eight, with Luke, who showed up when he was sober. I remember only a few of the names – I was often bow, Seph was stroke, and, in the middle, Patrick (half-Swiss, from Coventry), French Ben (the life of any party, who, no matter how recently he shaved, always looked like he had a thick shadow on his jaw), Luke (who looked like Ricky Martin), Hugh (who always competed with Luke for everything, especially drinking and girls), Nicky (who was later barred from the all-you-can-eat Chinese restaurant because he could eat so much), and one other guy whose name escapes me now, but who was half-Chinese, like me. Everyone else – including my roommate, David, who dropped out of the university to work his family farm – disappeared within three weeks.

The lifestyle, in retrospect, could be interpreted as brutal. We had almost daily workouts which occasionally led to someone throwing up. Patrick had a car, which made commutes easier, and he would often drive us all out to Talybont or to the boat club, five people piled into his tiny hatchback, singing “I Try” by Macy Gray as loudly as we could. Because of the time demands, and the internal competition to be fit, there was little time to do anything but go to school, work out, row, and, on Thursdays, get drinks with the other people on our team before an extra-tough Friday night workout and a Saturday row.

But the lifestyle didn’t seem brutal at the time – only exciting and privileged. Just look at that dropout rate – nobody else could do what we were doing! And that sentiment made us keep going, made us keep training hard and encouraging each other. As a study-abroad student, too, I felt as if I was actually getting the full study-abroad experience, immersed in a group of British natives, depended upon for their very ability to perform. In the Spring semester, some students from Colgate came to study, and I was asked to show them around; Lindsay, the other Pitzer student in the autumn semester program, had moved on to Germany, whereas I had chosen to stay for the full year, solely because I didn’t want to let the crew down. I met with these Colgate students, and they told me about all of the trips they had planned – each weekend, it seemed, there was another outing, and they were excited to see everything. I remember being horrified by it all – how would they ever get to know anyone in Cardiff if they were gone three or four days a week? How would they ever understand Wales if they were trying to see Rome, or Berlin, or Madrid? And that showed me what, I think, I had prioritized – getting to be part of the community in Cardiff, not seeing it as a base for going to every other country in the EU within one semester but as a place to deeply integrate with. Even now, the idea of spending a few days or, as one of my friends recently did, a few hours in a city before moving on to the next one, revolts me. I would much rather stay in one place for a month than see four places for a week each.

Early on in that Cardiff year, over drinks, I noticed that French Ben had what looked like a very nice wallet. He got embarrased, said that his mother had bought it for him from some shop I had never heard of in Paris, and that she insisted that he use it; it was important to her that he have nice things. Then he turned toward me and lowered his voice, he confided that his family was originally nobility from what is now Austria; when the Habsburg empire fell, they had fled to Egypt, where they were protected until King Farouk was toppled. They fled to France, where he was born and raised; if I ever wanted to go, his mother would look after me like her own son. I remember being in the student union, drinking a Malibu and Coke, which was my default “I’m a 20-year-old American and drinking for me is illegal and this is the only thing that tastes halfway decent” drink, talking confidentially with exiled European royalty, and thinking: this is exactly the sort of thing that happens to me.

Years later, I went back to Cardiff to visit Patrick, and Ben came out on the train to join us. He was, by that point, working at some private bank in London, making unbelievable sums of money. When he saw that I still wrote with a fountain pen, he said that his bank had a ritual I might like: when someone was elected to be a partner, they were never told directly. Instead, when they arrived at work, they would find a new Mont Blanc fountain pen at their desk with a bottle of ink. Each partner had a unique color of ink they were assigned by the others, and, after making partner, they were expected to write only in that color; thus, anyone who read something in that color would know on sight who wrote it, and thus the partners never signed their names except on legal documents. Ben suggested that instead of the available-everywhere blue that I liked, I get a unique color of ink. On the one hand: how absolutely typical of private bankers in the early 2000s, how absolutely pompous; on the other hand: yes. So when we got off the train back to London, I went with him to a stationary shop near Piccadilly and asked to see all of their inks. Something brought me back to the Hannah Carter Japanese Garden, and the color scheme, and I chose brown as my ink color. Ben approved, and, to celebrate, we went out for a drink.

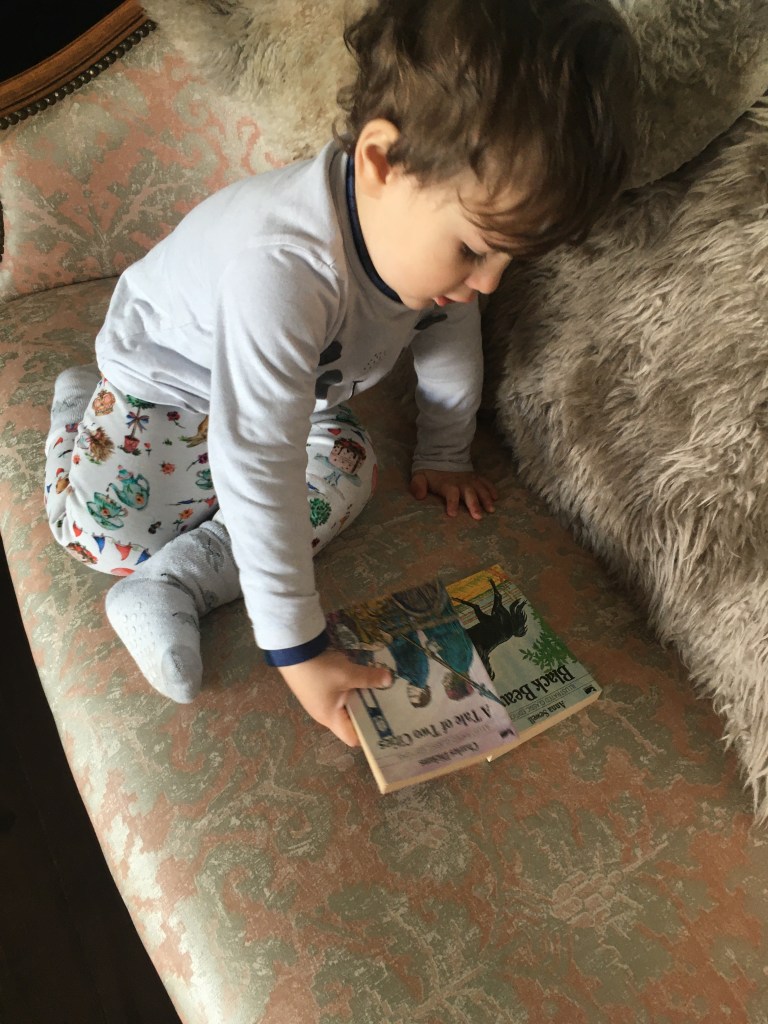

So I wrote almost exclusively with brown ink for about 22 years, until last year, when I also got a bottle of green ink, which seems less Autumn and more Spring. And Daniel, you may not remember this when you are reading this in the future, but when you were four, about to turn five, you looked in my desk drawer and pointed at the bottles and said, “What are those, daddy?” and I could only explain that they were ink bottles, and show you how I use them to fill up my Cross Townsend fountain pen, which is different from the Parker ’51 that my grandpa gave my father when he left Mauritius and my dad gave me when I was just older than you and which I lost, to my eternal shame and regret, and is also different than the Parker ’51 which I bought at a flea market in Lisbon and I let you squeeze into the bottle so you could feel the way the ribs worked on the bladder while it filled, and I look forward to you and Nick both picking your own unique colors to write with, and maybe changing them over time, and I hope that this helps explain why.

I enjoyed this, as always

LikeLike